From a 1200-baud modem to TA2Web — see how The Afterburner BBS inspired a modern blog connecting curious minds to classic tech and nostalgia!

Indeed, The Afterburner and the Commodore 64 is why this website is here right now —

Before websites, before Wi‑Fi, and long before social media feeds that never seem to end, there was a time when going online — when ‘online’ wasn’t even a word yet — meant dialing a phone number to connect to another computer and hoping you don’t get a busy signal.

For me, that journey began in the mid-1980s with my first home computers — a Commodore VIC‑20, followed later by a Commodore 64, a couple 1541 Floppy Disk Drives — and a 1200‑baud Avatex Modem that quietly connected my home computer to someone else’s home computer over a standard telephone line.

There were no browsers, no graphics, well there were minimal graphics, and no endless scrolling — it was all just endless uploading and downloading – something.

Once the connection was made, a screen very similar to a ‘website’ we see and know today, appeared on the screen. But instead of loading information from some server somewhere, you were actually connecting to someone else’s computer! That was the world of Bulletin Board Systems (BBS) before the internet — one user at a time over one phone line with no call waiting.

And well, I didn’t just dial into BBS systems back then — I ran one. That experience shaped how I think about online communities and websites to this day.

What Were Bulletin Board Systems?

Bulletin Board Systems were one of the earliest forms of online communication. Users connected directly to another computer using a modem and a phone number, logged in, and interacted with text-based menus, or BBS systems like CNet or All American BBS Software, to chat one on one, read messages, transfer files, and explore shared content. These systems predated the modern internet and were largely standalone systems tied to individual phone numbers connected to a business or someone’s early version of a PC.

Unlike today, there was no global network — each board was its own destination, it’s own entity. You needed its number and the patience to dial in, sometimes across city lines, even state lines. Access was the gateway; geography mattered less than having a working connection.

The First BBS and the Birth of Online Communities

The first widely recognized BBS was CBBS, launched in 1978 by Ward Christensen and Randy Suess in Chicago. CBBS used Christensen’s XMODEM protocol, which made reliable file transfers possible and helped establish many of the conventions that later online systems would adopt.

CBBS allowed users to leave messages, download files, and participate in the first generation of online communities. Everything was text-based, slow by modern standards, but it worked — proving that people wanted to connect this way.

Pioneering BBS Software: CNet and All American BBS

As BBS culture expanded in the 1980s, different software platforms emerged, often tied to specific computer systems.

CNet BBS Software (Commodore 64 Era)

A popular favorite was CNet among Commodore 64 users. It offered messaging, file sharing, user accounts, and sysop controls on affordable hardware. One of its biggest strengths was being written in BASIC, allowing sysops to tweak menus, commands, and features to give each board its own personality. Hierarchical message boards and customizable user levels helped create organized communities.

All American BBS Software (Commodore 64 Era & The Afterburner)

All American BBS was widely used for its stability and ease of setup. I ran The Afterburner on a Commodore 64 using All American BBS. The software provided the core functionality needed to operate a board: user logins, message areas, file transfers, and system management tools.

What made it unique was the customization we added. My friends and I spent hours coding our boards with BASIC and special p-files to enhance features, add personality, and make them more engaging. Every board felt different — almost like an early website, crafted by hand.

Life on a BBS: One Connection, Anywhere a Phone Could Reach

Most bulletin board systems could only handle one caller at a time, so busy signals were common. Weekend nights could see up to a dozen calls, and connections sometimes lasted hours for large file transfers.

Users typically communicated via live chat during active sessions, while leaving messages if the sysop wasn’t available. I remember sharing and discussing text adventure games like Zork, swapping tips, and enjoying the shared excitement of solving puzzles through text alone.

Dial-up culture also had its quirks: modems made their distinctive handshake noises, and connection errors could frustrate or amuse. Some enthusiasts explored phone line phreaking, testing ways to reach systems or unlock hidden behaviors, which added a layer of adventure and technical curiosity.

Every login was an exercise in focus: check messages, upload or download files, leave notes, and log off promptly so someone else could connect. These practices fostered a sense of responsibility, patience, and community etiquette — lessons that still influence how I view online spaces today.

The Commodore 64 and the BBS Experience

The Commodore 64 played a huge role in BBS culture. Affordable, widely available, and powerful for its time, it became the natural choice for both sysops and users.

BBS software transformed the C64 into a communications hub. With a modem connected, a C64 could accept calls, manage user accounts, store messages, and host file libraries — all within extremely tight hardware constraints. The keyboard, text-based screens, and memory limits shaped how BBS systems looked and behaved. It wasn’t about speed or visuals — it was about access, reliability, and interaction.

A Personal Note: Running The Afterburner BBS

During this era, I ran my own bulletin board system called The Afterburner on a Commodore 64 using All American BBS software. With a single phone line and a 1200-baud modem, the system answered calls one at a time.

Running a BBS meant mastering the quirks of hardware, software, and the modem. I spent hours coding, customizing p-files, and tweaking features to make the board unique. There were no special events that I remember but there were some themes, everyone had their own personality with their boards just like webmasters have their own thing with their websites today. It was just the everyday excitement of sharing software, games, and chatting, More like a software exchange it was for me.

Weekend nights could see up to 12 call attempts (though only one could connect at a time), and some sessions lasted hours for file transfers. It was hands-on, sometimes frustrating, but incredibly rewarding to see people return night after night, connect, and participate. Boards could answer automatically and didn’t need their sysop there 24/7.

Are There Still BBS Resources Today?

Yes — and more than you might expect. Enthusiast communities and archives preserve BBS software, manuals, and history, especially from the Commodore era. Notable resources include:

- C64 Wiki — history of CNet and manuals

- JLedger PETSCII Forum — Commodore and PETSCII culture

- Zimmer’s Net — archives related to BBS and CNet development

- Port Commodore — BBS documentation and articles

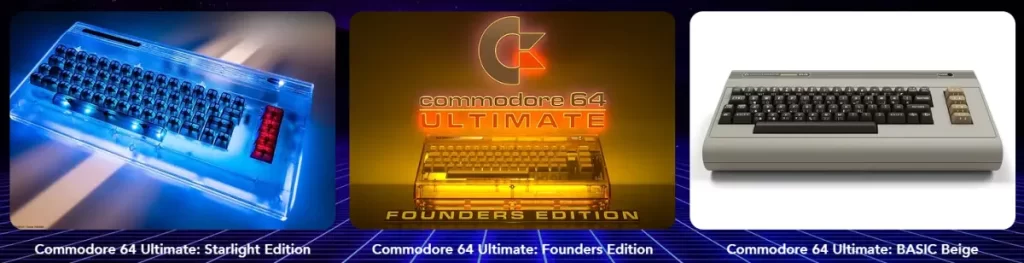

- Commodore Inc. — modern revival of Commodore

Why BBS Systems Still Matter

Bulletin Board Systems weren’t just a stepping stone to the modern internet — they were the foundation. Concepts like online identity, moderation, digital communities, and shared spaces existed long before the web.

For those who experienced it firsthand, BBS systems were learning environments, social spaces, and the first real taste of being connected — one phone call at a time. For me, The Afterburner BBS is the reason TA2Web exists today, connecting people with content and communities inspired by those early digital experiences.